Next time you get a really big electricity or gas bill, your thoughts may turn to solar panels. Wouldn’t it be good if you could catch all the power you need from the Sun? Millions of people already do get their energy this way, though mostly in the form of heat rather than electricity. Solar electric panels (also called solar cells or photovoltaic cells) that convert sunlight to electricity are only just becoming really popular; solar thermal panels, which use sunlight to produce hot water, have been commonplace for decades. Even in relatively cold, northern climates, solar hot-water systems can chop significant amounts off your fuel bills. Typical systems generate anything from 10–90 percent of your hot water and pay for themselves in about 10–15 years (even sooner if you’re using them for something like a swimming pool). Let’s take a closer look at how they work!

How to build a solar heating system

Imagine you’re an inventor charged with the problem of developing a system that can heat all the hot water you need in your home. You’ve probably noticed that water takes a long time to heat up? That’s because it holds heat energy very well. We say it has a high specific heat capacity and that’s why we use it to transport heat energy in central heating systems. So can we devise a simple solar heating system using water alone?

Stand a plastic bottle filled with cold water in a window, in the Sun, and it’ll warm up quite noticeably in a few hours. The trouble is, a bottle of water isn’t going to go very far if you’ve a house full of people. How can you make more hot water? The simplest solution would be to fill lots of bottles with water and stand them in a row on your window-ledge.

Or maybe you could be more cunning. What if you cut the top and bottom off a plastic bottle and fitted pipes at each end, feeding the pipes into your home’s hot water tank to make a complete water circuit. Now fit a pump somewhere in that loop so the water endlessly circulates. What will happen is that the sunlight will systematically heat all the hot water in your tank (although it’ll never get particularly warm because plastic bottles standing on window-ledges aren’t that brilliant at collecting heat). But, in theory, you’ve got a working solar heating system here that’s not a million miles away from the ones people have installed on their homes. It’s very crude, but it works in exactly the same way.

The parts of a solar-thermal hot-water system

In practice, solar heating systems are a little bit more sophisticated than this. These are the main parts:

Collector

Photo: A typical solar hot water panel uses a flat-plate collector like this. Photo by Alan Ford, courtesy of US Department of Energy/National Renewable Energy Laboratory (DOE/NREL).

This is the technical name for the big black panel that sits on your roof. Smaller homes (or ones in hotter climates) can get away with much smaller panels than larger homes (or ones in colder climates); typically collectors vary in size from about 2–15 square meters (~20–160 square feet). Not surprisingly, collectors work most efficiently on roofs that have a direct, unblocked view of the Sun (with few trees or buildings in the way). Broadly speaking, there are two types of collectors known as flat-plate and evacuated tube.

Flat-plate collectors

Flat plates are the simplest collectors: at their most basic, they’re little more than water pipes running through shallow metal boxes coated with thick black glass. The glass collects and traps the heat (like a greenhouse), which the water running through the pipes picks up and transfers to your hot water tank.

Evacuated tubes

These are a bit more sophisticated. They look like a row of side-by-side fluorescent strip lights, except that they absorb light rather than giving it out. Each tube in the row is actually made of two glass tubes, an inner one and an outer one, separated by an insulating vacuum space (like vacuum flasks). The inner tube is coated with a light-absorbing chemical and filled with a copper conductor and a volatile fluid that heats up, evaporates, carries its heat up the inner tube to a collecting device (called a manifold) at the top, where it condenses and returns to the bottom of the tube pick up more heat. The manifold collects the heat from the whole row of tubes and ferries it to your hot water tank. Unlike flat-plate collectors, evacuated tubes don’t let as much heat escape back out again, so they’re more efficient. However, since they’re a bit more hi-tech and sophisticated, they are usually much more expensive.

Photo: An evacuated-tube collector. Note the gray manifold at the top and the white water pipe flowing through it. Photo by Kent Bullard, courtesy of US National Park Service and US Department of Energy/National Renewable Energy Laboratory (DOE/NREL). Artwork: How it works: a number of parallel, evacuated tubes (blue) receive concentrated solar energy from parabolic reflectors either side (yellow), which they send to a combined heat-exchanger and manifold (brown), through which hot water (or some other fluid) flows from entry and exit pipes. Artwork from US Patent 4,474,170: Glass heat pipe evacuated tube solar collector by Robert D. McConnell and James H. Vansant , US Department of Energy, October 2, 1984.

Artwork: A closer look at how an evacuated tube collector works. 1) The copper in the inner tube absorbs solar heat and evaporates the volatile fluid. 2) The evaporated fluid rises up the tube to the manifold at the top and gives up its heat. 3) Water flowing through the manifold picks up heat from all the tubes plugged into it. 4) The fluid condenses and falls back down the tube to repeat the process.

Hot water tank

There’s no point in collecting heat from your roof if you have nowhere to store it. With luck, your home already has a hot-water tank (unless you have a so-called gas “combi” boiler that makes instant hot water) that can be used to store heat from your collector; it’s a kind of “hot water” battery that you heat up at conveniently economic times (usually at night) ready for use during the day. If you don’t have a hot-water tank, you’ll need to have one fitted. The more people in your household, the bigger the tank you’ll need. A typical tank for a family home might be about 100–200 liters (30–60 gallons).

Heat exchanger

Typically, solar panels work by transferring heat from the collector to the tank through a separate circuit and a heat exchanger. Heat collected by the panel heats up water (or oil or another fluid) that flows through a circuit of pipes into a copper coil inside your hot-water tank. The heat is then passed into the hot water tank, and the cooled water (or fluid) returns to the collector to pick up more heat. The water in the collector never actually drains into your tank: at no point does water that’s been on your roof exit through a faucet!

Photo: A different and much bigger solar hot-water system. This one uses parabolic mirrors to collect the Sun’s energy and focus it onto water pipes running through their centers. The water is pumped back to the building in the background (Jefferson County Jail in Golden, Colorado). Photo by Warren Gretz courtesy of US Department of Energy/National Renewable Energy Laboratory (DOE/NREL).

Pump

Water doesn’t flow between the collector and the tank all by itself: you need a small electric pump to make it circulate. If you’re using ordinary electricity to make the water flow, the energy consumed by the pump will offset some of the advantage of using solar-thermal power, reduce the gains you’re making, and lengthen the payback time. Cleverly, some solar-thermal systems use solar-electric (photovoltaic) pumps instead, which means they are entirely running on renewable energy. A good thing about a design like this is that the solar pump is most active on really sunny days (when most hot water is being produced) and less active on cold, dull days (when, perhaps, you don’t want your solar panel to be working at all).

Control system

If it’s the middle of winter and your roof is freezing cold, the last you thing you want is to transfer freezing cold water into your hot water tank! So there is also generally a control system attached to a solar-thermal panel with a valve that can switch off the water circuit in cold weather. A typical control system may incorporate some or all of the following: a pump, flowmeter, pressure gauge, thermometer (so you can see how hot the water is), and thermostat (to switch off the pump if the water gets too hot).

How solar-thermal panels work

In theory

Here’s a simple summary of how rooftop solar hot-water panels work:

- In the simplest panels, Sun heats water flowing in a circuit through the collector (the panel on your roof).

- The water leaving the collector is hotter than the water entering it and carries its heat toward your hot water tank.

- The water doesn’t actually enter your tank and fill it up. Instead, it flows into a pipe on one side of the tank and out of another pipe on the other side, passing through a coil of copper pipes (the heat exchanger) inside the tank and giving up its heat on the way through.

- You can run off hot water from the tank at any time without affecting the panel’s operation. Since the panel won’t make heat all the time, your tank will need another source of heating as well—usually either a gas boiler or an electric immersion heater.

- The cold water from the heat exchanger returns to the panel to pick up more heat.

- An electric pump (powered by your ordinary electricity supply or by a solar-electric (photovoltaic) cell on the roof keeps the water moving through the circuit between the collector and the water tank.

In practice

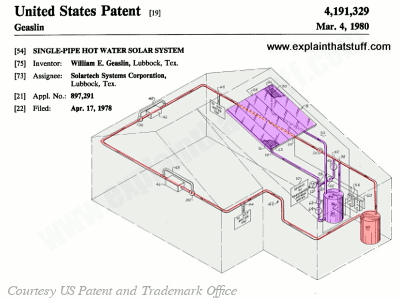

Artwork: A single-pipe solar heating system. Artwork from US Patent 4,191,329: Single-pipe hot water solar system by William E. Geaslin, Solartech Systems Corporation, published March 4, 1980, courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

Of course, it’s a bit more complicated than this! What if it’s winter and there’s no useful solar heat outside? You don’t want the solar system pumping cold water down into your home, but you still need hot water. And what if it’s really cold? You’ll need to stop your solar system from freezing up, so it would be useful to pump hot water from your home through it occasionally. That’s why a typical solar system will look more like this one, with two interlinked water circuits. One (purple) pumps water through a solar panel as we saw above and down into a tank inside your home. This is connected to a second circuit (red) with a conventional hot water tank that can be heated by electricity, a natural gas furnace, or some other standard form of heating. On hot days, you effectively capture hot water in the purple circuit and then divert it around the red circuit into your home. On cold days, you can switch off the purple circuit using various valves or divert water from the red circuit through the purple circuit to stop it from freezing.

How good is solar thermal?

“… One of the most effective and efficient steps the government can take is to encourage the use of solar hot-water systems—a well-developed and relatively low-tech method for using the sun’s energy.”

Larry Hunter, The New York Times (Op Ed), 2009

In pure efficiency terms, solar-thermal panels are over three times as efficient (50 percent or so) at harvesting energy as solar-electric (photovoltaic) panels (typically around 15 percent), but that doesn’t mean they’re three times better: it all depends what you want from solar energy. If you live in the kind of family home where people are taking baths and showers all the time, especially in summer, solar thermal makes perfect sense. A decent system should be able to produce around half to two thirds of a home’s total, annual hot water needs (all your hot water in the height of summer and very much less in winter). The obvious drawback of solar thermal is that it produces nothing but hot water—and you can only do so much with that; unlike photovoltaics, solar-thermal panels can’t help you heat your home or produce truly versatile, high-quality energy in the form of electricity. The typical payback time for solar thermal (when your original capital investment has paid for itself in fuel savings) is about a decade, with a range of 5–15 years (depending on the cost of the fuel you’re saving, how much sun your home gets, and how much hot water you use).

Here’s a very rough comparison of the payback times for different types of green energy. It does depend entirely on what you’re installing, what you’re replacing, what existing fuel you’re not using instead, how much you used the old and new systems, and various other factors (such as tax incentives), so please don’t take the figures too literally.

| Measure | Payback |

|---|---|

| Solar hot water | 5–30 years |

| Solar photo voltaic | 8–25 years |

| Loft insulation | 2–5 years |

| Cavity wall insulation | 2–3 years |

| Small wind turbine | 5–15 years |

| Ground source heat pump | 10–50 years |

| Wood burner | 2–5 years |